18th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2023 – The best pavilions

18th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2023 – The best pavilions

Entitled ‘The Laboratory of the Future’, the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale has caused much controversy. Many defined it as “an architecture biennial without architecture” and deplored an excessive presence of “pseudo-art” and a lack of concrete proposals. I am not very interested in digging into what others already discussed comprehensively, but I prefer to focus on what I’ve found interesting during my visit to (and outside) this year’s Biennale.

The best national pavilions

Pavilion of Belgium – “In Vivo”

In a world in which resources are more and more scarce, the pavilion curators – Bento and the philosopher Vinciane Despret – present an original and challenging project in which organic matter, fungi, and raw earth have been used to create innovative construction materials, eco-friendly and low-cost aimed to replace traditional ones. The pavilion features a large space clad with tiles made from mycelium and raw earth together with an experimental facility that produces an organic building skin out of mycelium.

The Belgian Pavilion “In Vivo”, Venice Architecture Biennale 2023; the central space, clad in organic tiles, and mycelium tile samples; photos © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

Pavilion of Germany -“Open for maintenance”

Curated by Arch+ / Summacumfemmer / Büro Juliane Greb, the German Pavilion has been transformed into a workshop on the reuse of building materials.

Converted into a warehouse in which scrap materials and installation elements collected from forty pavilions of the latest edition of the Art Biennale have been stored, the German Pavilion is also a laboratory aimed to investigate strategies for the reuse of construction materials throughout Venice.

German Pavilion “Open for maintenance”; the recovered material “warehouse” and the recycling/upcycling workshop; photo © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

Pavilion of Switzerland – “Neighbours”

Karin Sander and Philip Ursprung, the Swiss Pavilion curators, have removed a portion of the wall that separates the Swiss Pavilion from the Venezuelan one, creating a passage between them. Their action emphasizes the spatial and conceptual proximity of the two pavilions together with the friendship between Bruno Giacometti and Carlo Scarpa, the two architects that designed them.

Swiss Pavilion “Neighbours”; a view of the new passage towards the Pavilion of Venezuela and an interior view of the exhibition; photo © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

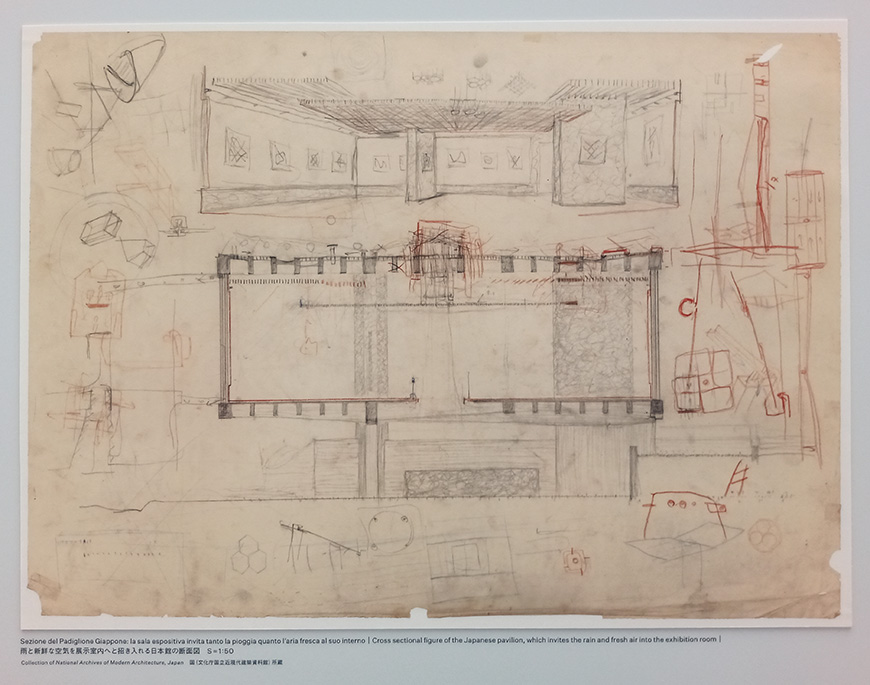

Pavilion of Japan – “Architecture: a Place to be Loved”

Like the pavilions of Switzerland and Germany, also the Japanese Pavilion – designed by Takamasa Yoshizaka in 1956 – focuses on its building. Curators Maki Onishi and Yuki Hyakuda, through an exhibition that presents the history of the pavilion’s design and construction and by creating contemplative places under and around the pavilion, tell us that architecture is, above all, a place to love and to take care of.

Japanese Pavilion “Architecture: a place to be loved”, interior and exterior views of the pavilion and an original drawing of the pavilion project by Takamasa Yoshizaka; photo © Federica Lusiardi/Inexhibit.

Pavilion of Brazil – “Earth”

Winner of the Golden Lion and curated by Gabriela de Matos and Paulo Tavares, the Pavilion of Brazil is an ode to the earth. Earth as a building material that made up the pavilion’s floor and rammed-earth tables and benches and which permeates the pavilion with its fascinating smell, and Earth as our common home.

“Our proposal is based on the idea of Brazil as Earth. Earth as soil, fertilizer, land. Earth in a global and cosmic sense, as a planet and common home of life, human and not”, the curators say. Developed in collaboration with indigenous communities, the installation presents Brazil as a country with a long history, compares the indigenous building culture with the modernist architecture of the pavilion, and criticizes the myth of Brazilia as a capital built from nothing, since to make room for it an entire indigenous community was forcibly displaced.

Brazilian Pavilion “Earth”, a global view of the installation and a close-up of one of the rammed-earth dwarf walls. photo © Riccardo Bianchini e Federica Lusiardi.

Pavilion of Turkey – “Ghost Stories. The Carrier Bag Theory of Architecture”

The exhibition in the Turkish Pavilion is an interesting reflection on the reuse of abandoned buildings. In Turkey, the construction industry is driven by economic growth, and a large number of new buildings are continuously made despite the presence of many disused ones. The exhibition, curated by Sevince Bayrak and Oral Göktaş, is an invitation to listen to the stories of abandoned buildings, and rethink and reinterpret a number of disused structures, now in a state of neglect, which may help revitalize entire urban areas.

The Turkish Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, installation view; photo © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

Pavilion of Austria – “Beteiligung”

The project to connect the Austrian Pavilion with the Sant’Elena neighborhood of Venice sadly did not succeed. The idea was to open the Biennale to the city of Venice allowing the local population, from May through November, to freely access a part of the Biennale Gardens, which originally were open to all. Developed by AKT & Hermann Czech with the support of a local architect, the original project – which included the realization of a new pedestrian bridge directly connecting the pavilion with the Sant’Elena neighborhood – was not fully supported by the Venice Biennale and did not obtain the required planning permission.

Austrian Pavilion, a view of the pavilion with, in the background, the only portion of the “bridge” that was possible to build, and a view of a scale model of the original project; photo © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

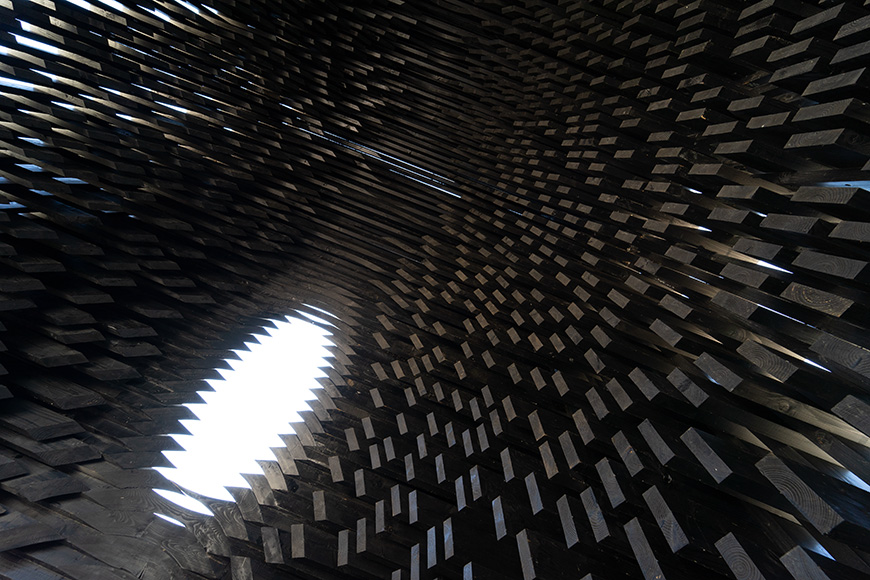

Kwaeε, The Black Pyramid pavilion by Adjaye Associates at the Venice Arsenal

In the twi language, one of the most spoken Ghanaian dialects, Kwaeε means “forest”. The wood structure of the pavilion designed by Adjaye Associates creates patterns of lights and shadows that evoke the sensation of walking in a forest. A triangular prism externally, the pavilion internally is shaped as a rounded cocoon, or a cavern, and has been conceived for people to meet and relax, as well as to accommodate special events.

Exterior and interior views of Kwaeε, the timber pavilion designed by Adjaye Associates for the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale; phot © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit.

Essential Home prototype – Norman Foster Foundation + Holcim

The Essential Home Project, developed by Norman Foster Foundation and Holcim, is presented at Palazzo Mora – in the Time, Space, Existence exhibition – and at the Giardini dell Marinaressa gardens – where a full working prototype has been installed.

The project is aimed at creating housing units providing safety, comfort, and well-being for the millions of people forced to live in displacement in refugee settlements, sometimes for decades.

The housing unit is composed of an external shell made of canvas impregnated with low-carbon cement that stiffens with water. The project is based on incremental modularity and consists of a basic structure that can be updated and expanded with time to adapt to the changing needs of its users.

Exterior and interior views of the Essential Home prototype designed by the Norman Foster Foundation in collaboration with Holcim and its model and material samples on view at Palazzo Mora in the “Time, Space, Existence” exhibition; photos © Riccardo Bianchini e Federica Lusiardi.

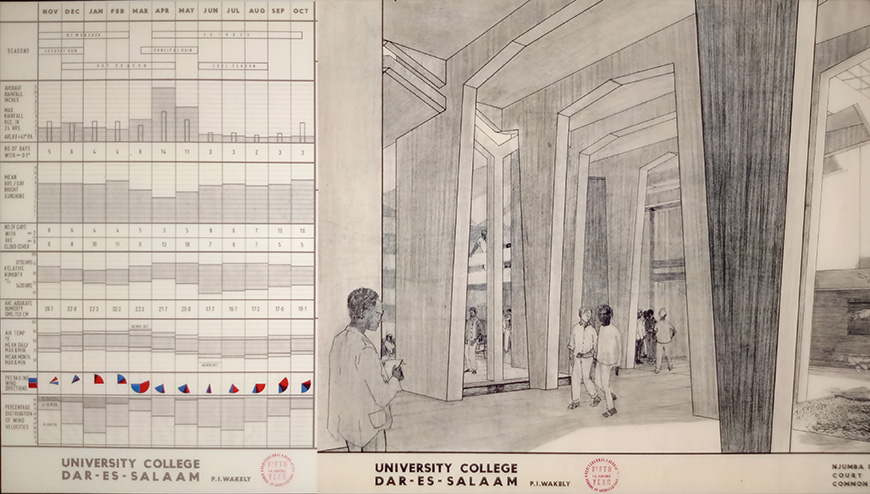

Tropical modernism. Architecture and Power in West Africa

At the Venice Arsenale, the “Tropical modernism. Architecture and Power in West Africa” exhibition, curated by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – Christopher Turner (Lead Curator, V&A) Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed (AA) – in collaboration with the Venice Biennale, presents the history of the Tropical modernism architectural movement.

Along with publications, projects, and original documents, the exhibition features an interesting documentary that traces the history of an architectural style initially aimed to back British colonization but later – after the independence of Ghana, the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to break free from colonial rule in 1957 – was adopted and further developed by west-African architects.

Tropical Modernism originated in British West Africa where, in the early 1940s, architects Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew developed a new style by adapting European modernist architecture to the hot and humid climate of Western Africa.

Their architectural language – based on solutions to control the hot climate such as adjustable ventilation louvers, large roof overhangs, and brise-soleils which reveal a superficial understanding of the African territory – was further developed at the Tropical Architecture Department they founded at the AA in London in 1954 and aimed to taught European architects how to design in the colonies.

The architecture of Fry and Drew gained international interest and the couple got many important commissions for schools, universities, civic centers, and libraries in Africa, mostly funded through the Colonial Welfare and Development Act – a 200-million-pound postwar program officially conceived to reform and modernize the British colonies but actually aimed at discouraging the quest for independence of the colonies as well as at making them more economically productive.

Tropical modernism. Architecture and Power in West Africa; Venetian Arsenale, installation views; photos Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

Photo © Federica Lusiardi.

copyright Inexhibit 2024 - ISSN: 2283-5474