Colosseum – Flavian Amphitheater, Rome

Lazio, Italy

How our readers rate this museum (you can vote)

The Colosseum (Italian: Colosseo), or Flavian Amphitheater, in Rome, is a monumental building dating to the 1st century AD and one of the world’s most visited archaeological sites.

Above, the Colosseum at night, photo by Jacob Surland Fine Art Photographer (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

History – The construction of the Flavian Amphitheater

The name Colosseum dates back to the Middle Ages, the ancient Romans called the structure Amphitheatrum Flavium (Flavian Amphitheater), from the name of the Flavian dynasty to which the three emperors under whom the building was constructed belonged: Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian.

The amphitheater’s site was previously an artificial lake part of the Domus Aurea, the enormous residence built by Emperor Nero near the Roman Forum.

Construction works began in 72 AD under Vespasianus and the building was completed in 82 AD under Domitian; funding mostly came from spoils of war, including that from the Sacking of Jerusalem in 70 AD. The origin of the medieval name Colosseum is disputed, it could be either derived from the “colossal” size of the building or as a reference to a gigantic bronze statue of Nero standing nearby.

The Colosseum is the largest amphitheater ever built, with room for up to 50,000 people (some scholars estimate an even larger number of about 70,000). To keep track of a so large audience, each sector and seat had reference numbers that corresponded to those reported on the visitor tickets so that all spectators knew in advance where their places exactly were, not unlike what happens in modern opera houses and sports arenas; traces of the red paint used to mark those seat numbering are still visible today. Prominent Roman personalities had their private space, identified with their name or status and not by a number, including a special loge reserved for the emperor and his guests. The best positions were in the lower part of the tiered seating space, while the upper rows were reserved for the plebs.

This complex ticketing system was necessary also because the shows were always free and therefore highly popular among the common people, and to direct noblemen and personalities to the sectors reserved for them and not to mix up persons of different social classes was considered something to pay great attention to, at those times.

Reconstruction of the original aspect of the Colosseum, from an architectural model of imperial Rome on view in the Museo della Civiltà Romana; photo by seier+seier (CC BY-NC 2.0).

An aerial view of the Colosseum today; photo Aeroshot.it (CC BY-SA 4.0).

From the golden age to the sunset

Most popular events taking place in the Flavian Amphitheater included gladiator fights, mock battles (including naval ones, called naumachiae), capital executions, and animal fights, as well as less sanguinary spectacles such as theatrical performances, circus shows, and sports games.

Various types of shows alternate during the day, thus making necessary that complex system of service spaces, corridors, and rising stages (moved mostly manually with the aid of counterweights) located in the basement, whose remains we can still see in the middle of the Colosseum due to the loss of the sand-covered wooden floor which once paved the arena (the modern term arena comes from the same Latin word meaning sand, indeed). An underground passage then linked the basement level of the Colosseum to the gladiators’ building, known as Ludus Magnus, nearby.

To the best of our knowledge, the last shows took place in the Colosseum in 523 AD, though the structure could have been sporadically used for some time.

The end of the arena as a public venue was the consequence of various concurrent factors: the decadence and then the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, the consequent drop of the population of Rome from over a million people it had in the 1st century AD to few tens of thousands – so that the amphitheater became greatly oversized and impractical -, and the Christian clergy and new “barbaric” sovereigns disliked it for the bloody games for which the structure was once renowned and which eventually led to the end of the ludi gladiatori (gladiators’ games) across the whole former empire.

For example, this is what King Theodoric the Great wrote in 523 to Flavius Anicius Maximus, consul of Rome, about the Amphitheater Flavius and its games, granting the last known permission to host a fight show (in this case between men and animals) in the Colosseum while at the same time regretting about such use.

“actus detestabilis, certamen infelix, cum feris velle contendere (…) hunc ludum crudelem, sanguinariam voluptatem, impiam religionem, humanam, ut ita dixerim, feritatem (…) Hoc Titi potentia principalis, divitiarum profuso flumine, cogitavit aedificium fieri, unde caput urbium potuisset. (…) heu mundi error dolendus! Si esset ullus aequitatis intuitus, tantae divitiae pro vita mortalium deberent dari, quantae in mortes hominum videntur effundi”

“It is a detestable act and an evil contest to fight with wild animals (…) cruel game, bloodthirsty entertainment, blasphemous religion, human savagery we may call it (…) Princely power of Titus had poured a river of wealth into that building so large that it would have been enough to erect a capital city. (…) What a pitiable error of mankind! If it had been any true idea of Justice, as much wealth would have been spent on the preservation of people’s lives as it has been squandered on the killing of human beings.” (Cassiodorus, Variae, book V, 42; Latin to English translation by Riccardo Bianchini)

For hundreds of years, from the 6th century to the 18th century, the grandiose building was used as a quarry from which to extract building materials and decorative elements. Meanwhile, the amphitheater remains were adapted to different functions, partially converted into houses, and sometimes still used as an impromptu performance venue; yet, it was mainly considered a monumental backdrop for religious celebrations and picturesque depictions of the city of Rome.

After the monument had been vandalized for some 1,200 years, in 1749 an edict by Pope Benedict XIV consecrated the ancient amphitheater, thus prohibiting its further spoliation and starting the process of restoration of the building.

In the second half of the 19th century, shortly after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, the Colosseum was forcibly deconsecrated and transformed into a public monument owned by the Italian State.

The amphitheater in the early 18th century in the painting “View of the Colosseum and the Roman Forum” by Dutch artist Caspar van Wittel (also known as Gaspare Vanvitelli), 1711, Galleria Sabauda, Turin; photo by Jean Louis Mazieres (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

The architecture of the Flavian Amphitheater

In ancient times, the Colosseum looked much different from now; its current aspect is the consequence of 20 centuries of aging, spoliation, and the earthquakes that hit Rome in 442, 484, 851, 1231, 1255, 1349, and 1703. The 851 earthquake was particularly destructive and caused the collapse of the two upper arcades on the south side, giving the building that asymmetric aspect it still has today.

Originally, the Flavian Amphitheater was a huge elliptic ring, 52 meters high and with a perimeter of 527 meters, covered with marble and travertine stone slabs and richly decorated with statues, reliefs, frescoes, and a series of gilded bronze shields called clipei.

The perimeter of the building was, and still is, marked by 3 rows of 80 large arched openings each, and by a top wall with 40 smaller rectangular openings. From bottom to top, the three lower rows are framed by Tuscan, Ionic, and Corinthian columns respectively, the fourth with more simple pilaster strips.

In the middle of the amphitheater stand the remains of an oval-shaped arena, whose major and minor axes were 86 meters and 54 meters (282 and 177 feet) long respectively, with an area roughly equal to that of 12 tennis courts.

The structure above the ground of the Colosseum is composed of an array of travertine stone pillars connected by groin vaults (among the first-ever built) made in the Roman precursor of modern concrete, the opus caementicium. The visible part of the building rests on a massive, about 30-meter-thick and 13-meter-high ring-shaped foundation made in Roman concrete (for the most part), bricks, and various types of rock, including travertine, basalt, and tuft. This sturdy structure explains why – despite its age, being built on a former lake bed, and several earthquakes – the amphitheater is still in rather good condition, at least from a structural point of view.

Not different from today’s sports stadiums, the public accessed the tiers of seats through a circulation system composed of side corridors, stairs, and passages called vomitoria (a quite ironic word roughly meaning pukers in Latin, alluding to the large crowd they “spewed” into the theater).

To protect the public from bad weather and sunshine, the amphitheater’s cavea could be partially covered with a retractable annular fabric canopy, known as velarium, fastened to an array of timber beams located on the upper level of the building.

The north side of the Colosseum gives the best idea of what the arena looked like in ancient times; photo Scott Taylor (CC BY-ND 2.0).

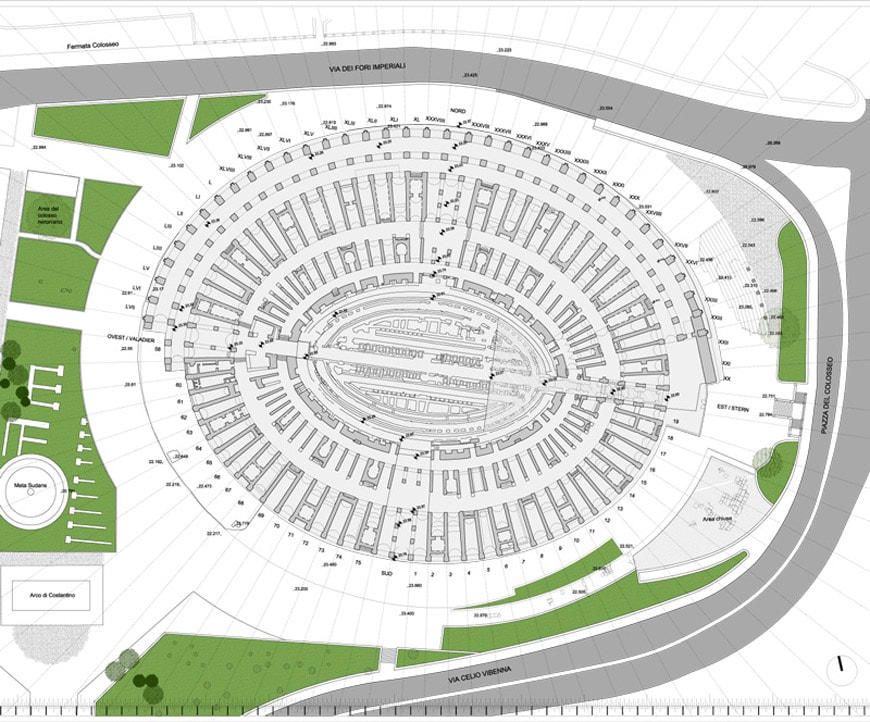

A general plan of the Colosseum from a recent survey; image MIBACT.

View from the southwest; photo Andy Withers (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Visiting the monument

With over 12 million visitors in 2024 (together with the Roman and Palatine fora, since the ticket is combined), the Colosseum is one of the world’s most visited archaeological sites. Due to conservation issues and safety reasons, access to the monument is currently limited to 3,000 people at once.

Unlike other Roman amphitheaters, such as the Verona Arena, the Colosseum is rarely used as a performance venue nowadays; yet, the site frequently accommodates special exhibitions and educational activities.

A typical tour of the Flavian Amphitheater usually includes visits to the covered passageways, the cavea, and part of the underground service spaces once located beneath the arena. Due to the popularity of the Colosseum as a tourist attraction, booking (online or by phone) is highly recommended.

Toilets, cloakrooms, audio guides, and a bookshop are available on-site; many parts of the building are accessible to physically impaired people. Security checks are usually quite tight; large backpacks and bags, trolleys, bottles, and alcoholic drinks are not allowed in the monument.

A curiosity: the Colosseum has been used as a location in many films, including Roman Holiday (1953, starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn), An American in Rome (1954, with Alberto Sordi), The Way of the Dragon (1972, starring Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris), Gladiator (2000, starring Russel Crowe, though the Colosseum was recreated in a set), and Jumper (2008, starring Hayden Christensen and Samuel L. Jackson)

View of the Colosseum arena and cavea, today; photo: daisy.images (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Colosseum, transverse section of the cavea

Interior views from the first gallery and the arena level; photos: Isriya Paireepairit (CC BY-NC 2.0).

View of a “vomitorium” from a circulation passageway; photo: Sara LaRosa (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Museums of Archaeology and Archaeological Sites around the World

copyright Inexhibit 2025 - ISSN: 2283-5474

(8 votes, average: 4,63 out of 5)

(8 votes, average: 4,63 out of 5)