Do Cities Dream of Plants? How to Fight Urban Heat Islands

Do Cities Dream of Plants? How to Fight Urban Heat Islands

On his way to work each morning, Marcovaldo walked under the green of a tree-lined piazza, a carved-out square of public garden in the midst of four roads. He looked up through the foliage of the horse chestnuts, where they were at their thickest and only let a glimmer of yellow rays penetrate the shade, transparent with sap, and he listened to the off-key racket of invisible sparrows in the branches. (from Italo Calvino, Marcovaldo: Or the Seasons in the City, Einaudi,1963)

Green space in cities has been an element of environmental quality for centuries; yet, in the past two decades, the role of vegetation has become even more important as urban forestation plans have emerged as effective strategies for combating heat islands, one of the most evident effects of climate change.

The Jardin des Tuileries in Paris; photo © Federica Lusiardi/Inexhibit

Heat islands in urban areas

Ongoing climate change has increased phenomena that we are already widely experiencing. One of the best-known is that of so-called ‘urban heat islands’ (UHI ), a definition that first appeared in the literature in 1958 in an article by Gordon Manley published in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. The phenomenon, which consists of a buildup of heat in urban areas relative to neighboring rural areas, is described by the term “island” because of the shape of the isotherms defining the areas with different temperatures, which make the city appear as an island in a “sea” of surrounding rural areas.

Pools and fountains in cities help mitigate reflected heat from buildings and hard-paved surfaces. In the picture: the Karmeliter Platz fountain in Graz, Austria; photo © Federica Lusiardi/Inexhibit

Factors affecting the formation of heat islands

The heat island is a thermal anomaly caused by many factors whose weight varies according to the characteristics of each urban area. The meteorological variables that most control the intensity of the phenomenon, and which it is not possible to intervene on, are wind speed and cloud cover, since they modify atmospheric turbulence and solar radiation, respectively. Instead, the causes related to anthropogenic changes in the territory, and therefore the subject of possible mitigation interventions, are related to variables such as urban geometry, thermal and radiative properties of the materials with which we make surfaces (buildings, pavements), vegetation reduction and energy processes that meet the needs of the population (traffic, heating, industries).

But why is the reduction of greenery one of the factors that increase heat islands?

In cities, the reduction of vegetated surfaces in favor of built-up surfaces results in a reduction of evaporation and transpiration processes that convert water into vapor by removing heat; urban surfaces are generally characterized by a high capacity to store heat that is released during the nighttime hours, in addition, the height and proximity of buildings cause multiple reflections of solar radiation thus increasing the albedo of the system, that is, the fraction of solar radiation incident on a surface that is reflected.

In the 2020 report by SNPA – Sistema Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente (National System for Environmental Protection), a chapter is dedicated to heat islands as one of the most significant consequences of land consumption.

The study highlights the relationship between the percentage of built-up area and temperature rise in urban areas and highlights that the presence of heat islands is related to several factors, such as type of urbanization, winds, altitude, and, of course, the presence or absence of vegetation. Net of regional differences, SNPA’s analyses show that summer diurnal LST (Land Surface Temperature) increases as the density of consumed land increases, and that areas with high density of consumed land have temperatures over 6 degrees higher than unbuilt areas.

“Land use is thus confirmed as a key component of ecological processes in urban areas, capable of modifying and creating new environments from a microclimatic point of view. LST is influenced by various factors related to land cover and elevation … but in general, it is evident that urban areas have significantly higher temperatures than non-urban areas.”(*)

(*) SNPA- National System for Environmental Protection. Land consumption, spatial dynamics, and ecosystem services. 2020 Edition.

Urban green space in northern Italy; photo © Federica Lusiardi/Inexhibit

The role of trees and vegetation

The presence of green areas in a city constitutes an element of heat island mitigation because trees located next to buildings help regulate their temperature. The effectiveness of vegetation and trees in cooling is determined by the sum of two main effects: shading and evapotranspiration. The effect of shading of deciduous vegetation exerts an important seasonal action in controlling solar radiation, providing summer shading to buildings and open-air areas, but allowing sunlight penetration in winter. The choice of essences is important, both because each species has different degrees of effectiveness in absorbing the most common pollutants and because the shape of the trees’ foliage, in combination with the shading coefficient, which depends on the density of the foliage, determines the total amount of shade.

Evapotranspiration is a process that involves the emission of water vapor into the atmosphere as a result of the utilization of solar radiation by plants. Plants, on average, use only 2 percent of solar radiation for photosynthesis, 20 percent is reflected or transmitted, and most, corresponding to about 68 percent, is re-emitted in the form of sensible heat and latent heat by evapotranspiration. With evapotranspiration, water contained in the plant, absorbed by the roots or intercepted by the atmosphere, is converted into vapor, thus removing heat from the plant and lowering its surface temperature. The fact that vegetation has lower temperatures than the surfaces of buildings and hard-surfaced areas reduces the heat input by radiation, convection, or conduction to the surrounding environment, improving environmental comfort.

Other benefits related to the presence of vegetated areas in cities should also not be underestimated: increased relative humidity, wind speed control, noise control, absorption of CO2 and other pollutants, oxygen production, and psycho-physical well-being.

Trees and the city, a view of the Porta Volta neighborhood in Milan with Herzog and de Meuron’s Feltrinelli Foundation in the background; photo © Riccardo Bianchini/Inexhibit

Urban forestation strategies in Italy

The issue of urban forestation has become central to the environmental policies of states, regions, and municipalities intending to reduce CO2 in the atmosphere and mitigate the effects of global warming. In Italy, the call to plant 60 million trees as soon as possible was promoted in September 2019 by three intellectuals – scientist Stefano Mancuso, Slow Food President Carlo Petrini, and Bishop Domenico Pompili of Rieti. The document echoed the initiative started by various international communities that were inspired by the ‘Laudato Sì’ encyclical published in 2015 by Pope Francis.

In July 2021, the Italian Ministry for Ecological Transition signed the decree funding thirty-four urban forestation projects with 15 million euros, including 14 proposed by the metropolitan cities of Venice, Bari, Genoa, Bologna, Palermo, Turin, Milan, Rome, Florence, Catania, Naples, Reggio Calabria, Messina, and Cagliari.

Two urban forestation projects in Italy

Milan, Metropolitan City – Forestami

The Forestami project plans to plant 3 million trees in the territory of the Metropolitan City by 2030, to counter the effects of climate change and improve the lives of the inhabitants of Milan and its entire hinterland.

Started in 2018 from a research by the Milan Polytechnic (Future City Lab of the Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, together with the Fausto Curti Urban Simulation Laboratory and under the scientific direction of Stefano Boeri) with the support of Fondazione Falck and FS Sistemi Urbani, Forestami is promoted by the Metropolitan City of Milan, Milan City Council, Lombardy Region, North Milan Park, South Milan Agricultural Park, ERSAF and Milan Community Foundation.

The Forestami project aims to promote a profound transformation of the urban fabric through interventions at different scales, which, alongside the implementation of urban greenery with the creation of green corridors, parks and tree-lined squares, also includes the conversion of school, university and hospital courtyards into green oases, the transformation of condominium courtyards and urban voids, the demineralization of paved and impermeable surfaces within commercial and industrial areas, the increase of green roofs and the remediation of polluted areas. Forestami is therefore an open project, which aims to involve the largest number of stakeholders, from public bodies to associations, from private companies to individual citizens and school students. Between 2018 and 2020, scientific, technical, and consultation activities were carried out with all interested municipalities, both to learn about the state of green areas within the Metropolitan Area and to develop pilot projects.

The official Forestami website (https://forestami.org/) reports that 610.083 trees have been planted as of April 2024.

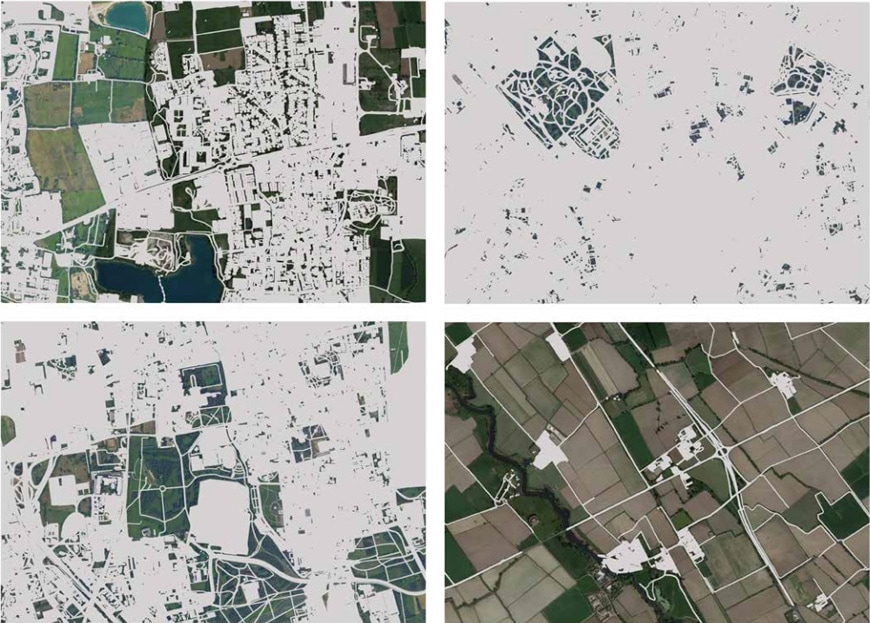

Impervious surfaces in four areas of the Milan Metropolitan City; Elaboration: Fausto Curti Urban Simulation Laboratory – Politecnico di Milano, from the Forestami 2020 Report

Prato – Urban Jungle

The Municipality of Prato’s Urban Jungle – PUJ project aims to redevelop and regenerate four districts of the city that suffer from greater social and environmental criticality through the increase of high-density green areas – so-called urban jungles – that will be implemented to harness the ability of plants to break down pollutants and improve the quality of the urban environment. The city government intends to co-design the interventions with the local community through shared urban planning. The four pilot sites chosen are: Rescue Neighborhood – Consiag Estra Headquarters; San Giusto Neighborhood – EPP Buildings via Turchia; Macrolotto Zero Neighborhood – Covered Market and Commercial Area of Via delle Pleiadi.

The project guidelines are presented in the Urban Forestation document, which contains both an in-depth analysis of the benefits of urban greenery by Stefano Mancuso and Pnat, and strategies for forestation intervention by Studio Stefano Boeri Architetti

With Urban Jungle, the municipality of Prato intends to achieve two main objectives:1, the regeneration of disused, underutilized or declining urban areas through the redevelopment and re-functionalization of buildings and spaces; 2, the creation of green hubs among the community capable of building facilities and areas of for environmental, sport, cultural and social activities.

The Prato Urban Jungle project was co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the Urban Innovative Actions program.

The official website https://www.pratourbanjungle.it/ reports all the info on the project’s progress.

Prato Urban Jungle, renderings of two projects: above, commercial area Via delle Pleiadi; below, Macrolotto zero-Covered Market

copyright Inexhibit 2026 - ISSN: 2283-5474