When did they get into our homes? A brief history of houseplants

When did they get into our homes? A brief history of houseplants

“More sun? Less sun? What do you want? More water? Less water? Why don’t you speak? Answer me now! (1)

My grandma loved plants. She kept dozens of them with their terracotta vases precisely aligned on the ground or suspended on iron frames close to the staircase. When I was young, I liked to see her taking care of red and pink hairy geraniums or repotting asparagus ferns and spider plants. She also cultivated flowers – small white roses, flowering quinces, asters, and jonquils – that in Spring and Summer gave her plenty of fresh bouquets she brought to the cemetery every Saturday afternoon.

Yet, there were no plants inside the house, not a single one. Plants were kept in the courtyard, on the terrace, and in our salad garden until late Fall, when they were moved laboriously to the attic where they rested, together with several pumpkins, all winter.

It was a country house with plenty of outdoor space, though. Furthermore, indoor planting was more popular in cities than in a small rural village. Things started to change in the late 1970s when the first houseplants popped up inside our house; they were mostly weeping figs and philodendrons climbing on thin brown stakes, that were watered by the means of strange spray bottles nobody had seen before. It was a small revolution.

While plants usually occupied the loneliest corner of the living room, their visibility has escalated in the last years. It’s probably too early to tell if the widespread passion for house plants of today is just a fad or expresses a novel and enduring respect for nature.

Certainly, demand has already created supply; both in the form of plants selected for their beauty and capability to adapt to indoor conditions and by the means of the countless containers, pots, supports, and accessories available on the web in all shapes and sizes.

As is widely known, most houseplants are native to the tropics; yet, the term “houseplant” is quite generic, since it is applied to very different species whose only common trait is their capability to survive in a small container place inside a room or on a balcony. Moreover, also houseplants vulnerable to fads and many of them link to a specific historical period, as we will discover later.

For sure, it’s more comfortable to live and work in greener spaces; it is reported that, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spring 2020, the request for houses with terraces and balconies has greatly increased and a terrace or a balcony do not make much sense without plants.

While the capability of plants to remove volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from the indoor environment is disputed – recent studies have found that certain potted plants absorb VOCs when placed in sealed chambers for a minimum of several hours (2) – there is no doubt that indoor plants improve people’s wellbeing, reduce stress and increase attention. Furthermore, we all know that taking care of plants is relaxing.

Junya Ishigami, ‘Extreme Nature. Landscape of Ambiguous Space”, Pavilion of Japan, 11th Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, installation view; photo © Inexhibit, 2009

New plants from the Empire

Although ancient civilizations already used potted plants, the idea to grow plants inside buildings became popular in the 17th century, when explorers returning from their travels and sailors coming back from the overseas colonies brought to Europe previously unknown species.

In the race to introduce new plants, Britons hold the lead for a long time, importing species from North America, Asia, Australia, and Africa. Among the most famous pioneers, Joseph Banks (1743-1820) introduced in Europe a number of tropical plants – including mimosas, eucalyptuses, and wattles -, and expanded the Kew Gardens, the world’s largest botanical collection. It is at that time that people began to cultivate plants indoors.

Up: houseplants in the Victorian era, images via www.oldhouseonline.com.

The Wardian case and the Victorian era

A further, decisive step towards the widespread diffusion of tropical plants, particularly suitable for indoor life, was made possible thanks to the invention of the Wardian case.

The Wardian case – invented in the 1830s by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, a London doctor with a passion for botany – was a sort of terrarium, a sealed glass case that provided an ideal environment for growing and transporting plants: in the hottest hours of the day, the soil layer inside the case emitted water vapor which consensed on the glass and then fell again on the soil, keeping it always humid and allowing the plants to survive and grow.

This apparently minor invention was crucial because it made it easier to import plants from other continents, thus changing forever how plants were cultivated in botanic collections throughout the world.

In the United Kingdom, exotic plants had a huge success during the Victorian era; they were cultivated in abundance in greenhouses, an iconic feature of Victorian gardens, and were ubiquitous in urban residences throughout the country. They were more frequently English ivy, dracaenas, and evergreen plants from China that did not require much daylight, instead of flowering plants. Other plants very appreciated in the Victorian era included ferns, widely used also to create floral arrangements in fireplaces in Summer and every sort of botanic architecture. We can get an idea of this crazy love for plants from the interior pictures of the time or the drawings of the Great Exhibition of 1851, where we see the Crystal Palace in London with its imposing greenhouse-like architecture filled with huge potted trees.

The Wardian case, image from Wikipedia.

Green spaces in the Victorian era: the Whittemore House. Image from Wikimedia Commons

Floral design between late-19th century and early-20th century and the Age of Kentia

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, a new trend bound up to the Art Nouveau style emerged. Nature in all its forms inspired applied arts – from textiles, furniture, and pottery to light fixtures, silverware, and fashion – as in the work of the artists of the Glasgow School, such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald, the furniture of Hector Guimard, and the stained glass of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

New artistic expressions were going hand in hand with technological and industrial developments, a new aesthetic sensibility arose and the congested Victorian interiors went rapidly out of fashion. The lush but unsophisticated domestic jungles of the 19th century made way for a more modern style that favored the elegant lines of the Kentia palm, a plant native of Australia which became very popular in upper-class residences and grand hotels in Europe and the United States. Also orchids – cited by Marcel Proust in his Recherche, and also appreciated by Tommaso Marinetti and Guy de Maupassant – were well-liked, and so were sansevieria, and lisianthus, a flowering plant discovered in the United States in the 19th century and widely cultivated commercially also in Europe.

The winter garden at the Ritz Hotel, London,1914. Image from Wikimedia Commons

A teacher’s room in the school of Vekkula, Finland, 1920, Image from Wikimedia commons

Green spaces in Modern Architecture

In the 1920s and 1930s, Modernist architects also focused on the relationship between architecture and nature. Especially in Northern Europe, plants and flowers found their place in winter gardens, glazed spaces that were no longer located outside houses but placed in the living room to be used all winter.

Among others, modernist buildings in which winter gardens play an important role include the Schminke House by Hans Scharoun built in Germany in the 1930s, the Tugendhat House by Mies Van der Rohe in Brno (1928-30), Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto in Finland (1937-1939), and the Electric House built in Monza in 1930 by Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini for the IV Triennale exhibition.

The project description of the Electric House (Casa Elettrica in Italian), which was built by the Edison Company as an experimental building and technology demonstrator, reads: “The large twin-glass wall of the living room, along with providing good protection against external temperature variations, is also a greenhouse for tropical plants that visually opens the house onto the surrounding landscape.”

Schminke House, the winter garden. Photo mksfca / Flickr

I’m just here to cater to the plants.

“And you’re doing a marvelous job. Although, that one is plastic. (4)

Glass vases with plants inspired by the principle of the Wardian case. Milan Design Week 2017, photo © Inexhibit

And now?

In the 1970s Italian movie series featuring the comic character Fantozzi, a clumsy salaryman working for a large corporation, the importance of the company’s employees could be inferred by the number of ficus trees in their office: “Seventh-level employee: mahogany-veneered desk, faux-leather chair, telephone, one ficus tree. Fifth-level employee: opalescent glass lamp, glass-top desk, one Naïve-art painting, two ficus trees. First-level employee: four ficus trees, three telephones, and one voice recorder, six Naïve-art paintings, wall-to-wall carpet. Director: private glasshouse with ficus trees and chairs made of human leather…” (5). It’s true that plants once mostly adorned upper-class residences; this is no longer the case, though; also in the small apartments plants have pride of space today, and moth orchids, for example, are on sale both in luxury plant shops on the main streets and in suburban discount stores.

Nero Wolfe – the fictional character created by Rex Stout in the 1930s, grew passionately expensive orchids in his New York home’s rooftop greenhouse; those orchids, that in Stout’s books were intended to symbolize exclusivity and rarity, are now among the most popular and bestselling flowers. Moreover, websites, design magazines, and social influencers regularly create lists of the most trendy plants, as if spiderworts and alocasias were skirts and coats.

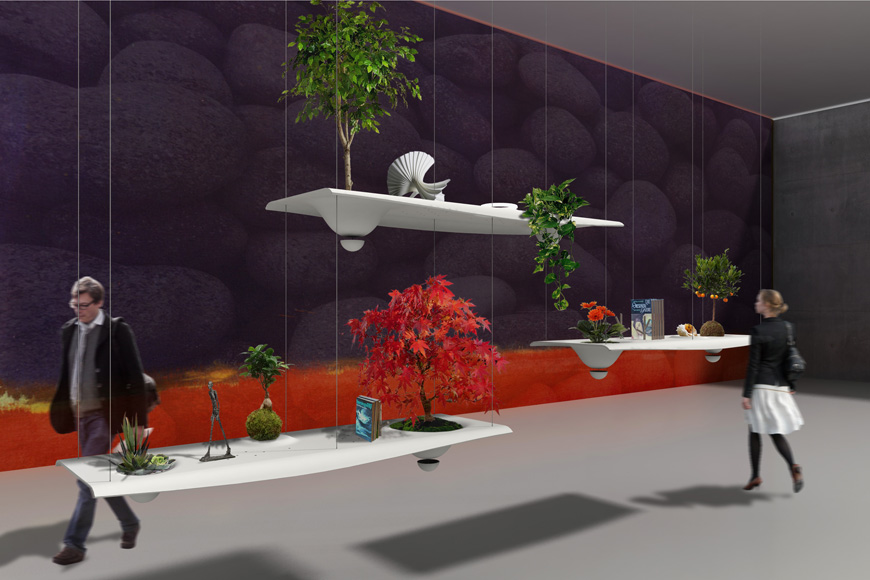

Bianchini e Lusiardi Associati, Landscape, plant container system, © BeL

Interestingly, there’s currently a successful trend, we could call “plant invasion”, which reminds us somewhat of the botanical abundance of the Victorian era interiors. Either to cope with today’s tight spaces or for aesthetic reasons, contemporary interiors are often shown as spaces literally flooded by plants – hanging, suspended, hovering on precarious supports, put inside glass bubbles, or hybridized with lighting systems. This aesthetic trend has been certainly influenced both by widely-published architectures, such as Stefano Boeri’s Vertical Garden towers and by more experimental projects presented in popular events such as the Milan Design Week and the London Design Festival.

We have to hope that the current “botanical renaissance” is more than a fad and that it is backed by the awareness that finding more sustainable ways of life and ways to build is not optional.

If I look out of the window, I see much we must do; though, while I dream of balconies transforming into gardens with people moving through them jumping from branch to branch like Italo Calvino’s Baron in the Trees, I console myself with the reflection that 80% of all biomass on Earth is made up of plants, and only 3% is composed of animals, including humans.

About the beneficial effects of plants on human beings, plant neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso writes: “The reasons why plants have these psychological benefits for us are still mostly unknown and may go back far in time, bound up in our unconscious awareness that without them life for our species wouldn’t be possible. The calm that pervades us in their presence may be the echo of an ancestral awareness that everything we need and every chance for our survival dwells in the green world. Now as long ago.” (6)

Notes

(1) From the movie Sweet Body of Bianca directed by Nanni Moretti, 1984

(2) See https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/pressroom/newsreleases/2016/august/selecting-the-right-house-plant-could-improve-indoor-air-animation.html), https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/44/5/article-p1377.xml, https://www.jsr.org/hs/index.php/path/article/download/1047/537, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5480428/

(3) Giacomo Polin, La casa Elettrica di Figini e Pollini, Officina Edizioni,1982

(4) From the movie Music and Lyrics directed by Marc Lawrence, 2007.

(5) FromThe second tragic Fantozzi, directed by Luciano Salce, 1976.

(6) Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence, Island Press, 2015

Estudio Campana, Sleeping Piles, installation view; University of Milan, 8-19 April 2019.

Photo by Riccardo Bianchini (Inexhibit.com).

To write this article, the following publications and websites were consulted:

– Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence, Island Press, 2015

– Bryan E. Cummings, Michael S. Waring, Potted plants do not improve indoor air quality: a review and analysis of reported VOC removal efficiencies, Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2020, under exclusive license to Springer Nature America, Inc. 2019

– Amanda O’Neill, Introduction to the Decorative Arts, Tiger Books International, London

– Mirella Serri, L’orchidea non è più peccato, published on La Stampa, 13 August 2009

– Giacomo Polin, La casa Elettrica di Figini e Pollini, Officina Edizioni,1982

– Pia Pera, Verdeggiando, curated by Lara Ricci, Il sole 24 Ore, 2019

– A brief history of house plants, from https://blog.leonandgeorge.com/

– https://www.oldhouseonline.com

– https://www.cakegardenproject.com/

If this content interested you, you can also read:

https://www.inexhibit.com/case-studies/interior-garden-design-hanging-and-vertical-garden-systems/

Cover image by Federica Lusiardi.

copyright Inexhibit 2024 - ISSN: 2283-5474