Design: Recycling vs Upcycling. What’s the difference?

What are the most recent results of upcycling?

A necklace by Japanese jewelry designer Eriko Unno, made by skilfully intertwining audio cassette magnetic tape and gold leaf. Photo © E. Unno

Design: recycling vs upcycling. What’s the difference?

What are the most recent results of upcycling? And how much does it really matter for today’s design?

People interested in design have probably heard the term upcycling, often opposed to recycling. Possibly, their reaction could have been: “Oh, just another of the many new words that sound cool but mean almost nothing”. But actually, the distinction between recycling and upcycling really makes sense and also invites us to investigate the very sense of terms such as product design and sustainability (*)

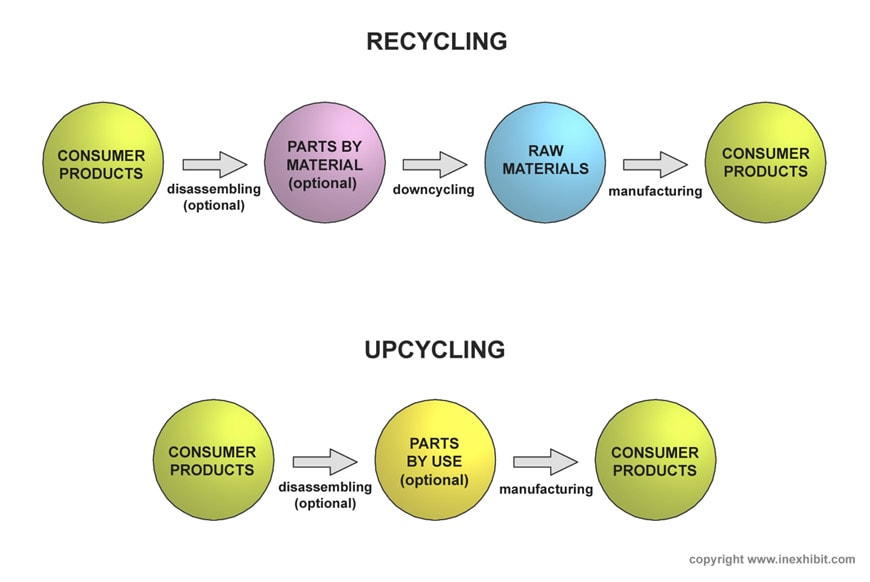

But, what makes the two terms differ from one another? To cut a long story short, I give a practical example. If we take a used glass bottle, melt it, and with the molten glass we make a lampshade, that’s recycling. If instead, we take the same bottle, clean it, and directly use it as the shade of our new lamp, that’s upcycling. In short, while recycling implies to reuse components of a product that – after being liquefied, crunched, and the like – were reduced to raw material, upcycling originates a new product by creatively reusing, all or in part, an object as it is; the resulting product can be either functionally similar to or very different from the old one. Marcel Duchamp would call it readymade, but the purpose of upcycling is not (or not only) making art.

A great advantage of upcycling is that, compared to recycling, the impact on the environment is reduced; downcycling – namely converting an object into raw materials, a fundamental part of the recycling process – requires a considerable amount of energy, indeed. (**)

Furthermore, the act of giving a product or even just parts of a product a second life, without the need for “degrading” it, is conceptually fascinating. There is an even more effective strategy: reuse. If we wash and sanitize our glass bottle and reuse it as a container, that would be the best solution. Those who bottle wine or jam “in-house” know it very well since they carefully store used bottles and jars for future use. As much an object is made up of a few materials and technologically simple as easier it will be to reuse it. Reusing a bottle “as it is” is easy, reusing a broken computer is more arduous. This would require me to introduce concepts such as products’ service life and planned obsolescence, but that would be a different story.

Back to the distinction between recycling and upcycling, from a conceptual point of view, upcycling provides things a second life, in the sense that they revive in the form of objects with a higher intrinsic value than what they had in their previous existence. Such a process of reinvention is even more valuable when the discarded pieces it is based upon are somewhat unique.

Only a few decades ago, especially in rural culture, what we call now upcycling was done commonly, for example taking the legs of a broken chair and joining them to other wood pieces to make a coffee table, thus creating objects that look bizarre, but are absolutely functional.

Of course, not everything can be upcycled, but, whenever it’s possible, upcycling is often a more efficient process with a lower impact on the environment compared to recycling.

Though the term was coined around twenty years ago, some designers of the 20th century conceived projects based on the principle of reusing objects well before. In 1992, Enzo Mari, with the “Ecolo” kit produced by Alessi, provocatively invited people to create flower pots from empty detergent bottles. For different reasons, also the approach of Achille Castiglioni is interesting. Since the early 1950s, ironically revisiting the artistic idea of the readymade, he took parts from various objects – a bike saddle, a tractor seat – “decontextualizing” and using them as components in his furniture designs. More recently, we can cite the seminal work of designer-maker Martino Gamper who, with his 2008 collection “100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways”, by combining theory and practice, brought the theme of furniture upcycling to international attention.

Martino Gamper, left: installation view from the exhibition ‘Transformers’, MAXXI Museum, Rome, 2015, photo © Inexhibit. Right: chair by the collection “100 Chairs in 100 Days and its 100 Ways”, 2008, © Martino Gamper.

(*)The term upcycling was coined in the late 1990s by Belgian Gunter Pauli and German Johannes Hartkemeyer (and later further developed by McDonough and Braungart in the early 2000s) as opposed to that downcycling, which in the recycling process indicates the conversion of a product’s material into a basic form, often of a lesser quality than the original one.

(**) Let’s give some numbers. Melting a couple of 750-milliliter glass bottles requires about 240Wh (about the same energy a cooking oven running at 200 C consumes in twenty minutes). It may seem not much, but if we consider that each person in the United States buys about 130 glass containers a year (28,3 kilograms in weight, 2011 data; source: EPA – the United States Environmental Protection Agency), this implies a total energy consumption of over 7 kWh / year and a Carbon dioxide emission of about 40 kilograms; per head. The calculation, which can be adapted to many other “recyclable” materials – including steel, aluminum, plastics, etc. – is pretty simple. Glass liquefies at about 1.300 Kelvin degrees (the exact temperature depends on the type of glass), considering a starting temperature of 300 K and a specific heat of about 0,24 Wh/kg °K, to melt a kilogram of glass (the weight of about two 0.75-liter bottles) requires 240W/h. Assuming that such energy is produced by a natural gas power plant, the CO2 output is about 120 grams.

But, what the most recent results of upcycling are? And how much does it really matter for today’s design? Some examples could shed some light on the matter.

The following example objects are made of materials from products discarded because worn out or obsolete. In these cases, the materials, which still retain their aesthetic and tactile properties, are chosen and combined to create a new product. The resulting objects combine a serial production process with elements that made each piece unique.

Re-Rag-Rug carpet, Milan design week, Ventura Lambrate, installation view, 2016, photo © Inexhibit

With its “Renew line”, Eileen Fisher presents its vision of a fashion based on the principles of the circular economy by reusing discarded clothes that are collected, cleaned, restored, and re-marketed. At the 2018 Milan Design Week, Eileen Fisher presented tapestries, textile wallpapers, dresses, and accessories made up of fabric remnants and used unsold or unfashionable clothes. https://www.eileenfisherrenew.com/

above: ‘Waste no more’, the Eileen Fisher‘s exhibition at Ventura Centrale, Milan, 2018, installation views, photos © Inexhibit.

Fabric remnants and scraps are often used to create unique pieces, real artworks. Based on reuse and upcycling philosophy, the work of Christina Kim is inspired by traditional craft techniques from all over the world.

On the left: the Eungie skirt designed by Christina Kim for Los Angeles-based company Dosa. Right: Kibiso Tsugihagi, 2016, design by Reiko Sudo, produced by NUNO Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). Reiko Sudo is the co-founder of Nuno, an innovative textile design company that combines traditional Japanese craft with advanced technology. Pictures from “Scraps: Fashion, Textiles and Creative Reuse” exhibition at Cooper Hewitt Design Museum, 2017.

Photos courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Design Museum.

The most radical form of Upcycling, namely that which collects and reworks garments, furniture, and small objects as identifiable artifacts, is particularly suitable for creating unique pieces.

Yet, in other cases, parts of products – such as electronic components from old consumer electronic devices – and scrapped materials, can be used like semi-finished materials which, despite having lost the original function for which they were originally produced, are still enough recognizable to suggest new creative possibilities for unique or limited edition objects.

Paola Sakr, “Impermanence vases”, a collection of concrete vases made up of recovered pieces; photos via http://www.paolasakr.design/; https://www.inexhibit.com/marker/maison-object-paris-6-emerging-designers-from-lebanon-for-the-next-rising-talents-awards/

Nelly Bonati, on the left, a necklace from the col-lane line made in wool and fabric; right: a necklace made up of fabric and plastic pieces collected on a beach presented in Karlsruhe at the “Just plastics…new uses” event, 2018. photo © N. Bonati

Federica Lusiardi Terrestre re-lamps. Above: suspended lamp / below: modular lamp O1S series. Both lamps are made up of recovered sheets of paper. photo © F. Lusiardi

Spark Architects, a kennel made up of used plastic bottles, designed for the British charity “Blue Cross for Pets”, https://www.inexhibit.com/marker/london-acclaimed-designers-artists-create-bespoke-dog-kennels-charity/

Serena Brigati, a necklace made up of discarded computer motherboards, photo © S. Brigati

Upcycling is not limited to products. In the last years, it has also been adopted in public temporary installations aimed to raise people’s awareness of sustainability.

above: Sa.und.sa, “Crazy shiny diamonds” – interactive installation consisting of empty plastic bottles presented at the “Ri-Festival 2012”, The discarded bottles were collected from trash bins in a shopping mall near Naples, selected one by one, and assembled to create interactive installations that were placed in the same mall the bottles were collected from. Images courtesy of studio Sa.und.Sa. https://www.inexhibit.com/case-studies/crazy-shiny-diamonds-an-installation/. Photo © Sa.und.sa

copyright Inexhibit 2024 - ISSN: 2283-5474